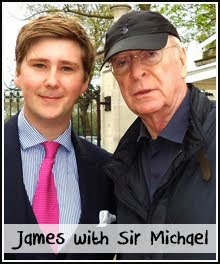

An interview with Sir Michael Parkinson, ‘The King of Chat’

My interview with 'Parky', as it appeared in

Cardiff University's Gair Rhydd newspaper in 2009

Interviewing Sir Michael Parkinson, as a humble trainee journalist, I imagine feels incredibly similar to the feelings felt by a school teacher waiting for an inspector during the first day of Ofsted.

As my stomach churned at the prospect of speaking to the ‘crème de la crème’ of journalism, there was a firm knock at the door. After a brief pause the door swiftly swung open. It was ‘Parky’. Well Sir Michael minus that theme tune, ‘Dat-diddly-da-da-da!’, his big-band intro and jaunty descent down the stairs that were synonymous with his long running hit television chat show, aptly named, ‘Parkinson’.

Entering the room with a certain air of authority, Sir Michael settled any early nerves I'd had with a simple smile and a firm handshake, saying jokily in true ‘Parkinson’ fashion, “It makes a change doesn’t it, to sit here and just wait for the other poor bugger to ask the questions.” At which I nodded and shared a mutual grin.

As we sat down to start the interview, with both seats facing each other as he always so famously did, I felt compelled to ask what had happened to those black swivel chairs that he, and pretty much everyone who was anyone, had sat on while he conducted his interviews.

“I actually bought two of the chairs that we used on the set, for £2,000, after we had finished the last show”, he said, shuffling in his seat as he tried to get comfortable. “I bought the interviewing chair, which I sat in, and the one I call David Beckham’s chair”, explaining, “His bum was on there.”

The thing that is so refreshing and charming about Sir Michael, the son of a Barnsley miner born in 1935, is that he is so perfectly human. As we begin to talk about his childhood, the room comes alive. He has a fascinating story to tell, and one that is just as enthralling as any of the celebrity guests he has questioned during his 36 years as ‘The King of Chat’.

The thing that is so refreshing and charming about Sir Michael, the son of a Barnsley miner born in 1935, is that he is so perfectly human. As we begin to talk about his childhood, the room comes alive. He has a fascinating story to tell, and one that is just as enthralling as any of the celebrity guests he has questioned during his 36 years as ‘The King of Chat’.

But for all the names, anecdotes and unrivalled insights into the world of celebrity, he humbly attributes his success to the efforts of his parents, who made him promise he would never go down the pit for a living.

Despite his Headmaster telling him he would ‘never amount to much’, he defied those who said he wouldn’t be anything other than a miner, by listening to his mother, and not only reaching for the stars, but talking to them too. His mother was, according to Sir Michael, “the engine” of his ambition. As he said, “She channelled all that ambition into me.”

Sitting back in his chair, he explains, “When you educate the working classes, stand back. Things will change."

Adding, “It was our generation that produced the 60’s, that wonderful explosion of working-class talent that overtook the arts and changed things. I couldn't have got a job at the BBC as a doorman, with my accent, for God's sake. But because of what happened, after a while you had to have an accent like mine to become a journalist at the BBC. That was transformation.”

Sir Michael, however, wasn’t the only one of his childhood friends to make a name for himself. It is no secret Sir Michael is a huge cricket fan and spent most of his youth playing in the same team as Geoffrey Boycott and Dickie Bird. “We were all at Barnsley together. It’s extraordinary now to look back on those days and to think we all had all the same ambition of playing cricket for Yorkshire and England, and to see how those two achieved their ambition and I didn’t.”

Sitting back in his chair, he explains, “When you educate the working classes, stand back. Things will change."

Adding, “It was our generation that produced the 60’s, that wonderful explosion of working-class talent that overtook the arts and changed things. I couldn't have got a job at the BBC as a doorman, with my accent, for God's sake. But because of what happened, after a while you had to have an accent like mine to become a journalist at the BBC. That was transformation.”

Sir Michael, however, wasn’t the only one of his childhood friends to make a name for himself. It is no secret Sir Michael is a huge cricket fan and spent most of his youth playing in the same team as Geoffrey Boycott and Dickie Bird. “We were all at Barnsley together. It’s extraordinary now to look back on those days and to think we all had all the same ambition of playing cricket for Yorkshire and England, and to see how those two achieved their ambition and I didn’t.”

Flicking through his autobiography, the most eagerly awaited showbiz memoir of the year, it is difficult to ignore the beautiful photographs, featuring those he has interviewed over the years. It gets me thinking whether there are ever situations where, for all the research he’s done, he’s met a guest and they’re completely different from the person he expected to meet.

After a short pause, Sir Michael leans back, shuffling around in his chair once again, and says, “I thought I'd fancy Meg Ryan more than I did. And vice versa (laughs). There was just a total lack of sympathy between the two of us.”

So what is it, I wondered, that separates those in the limelight from the rest of us, mere mortals in the background of life, rather than the forefront? “They have an indefinable quality that I describe as will power. If you look at Muhammad Ali, Nelson Mandela, Billy Connolly, there’s something that separates them from the rest of the human race. Although they are, of course, human, like the rest of us, they are special people, with an overwhelming drive to achieve something. I never had that drive. I just always wanted to be a good writer, a good journalist. That has been my motivation throughout my life.”

Despite being known as ‘the man who has met everyone’, there are a few, believe it or not, who escaped his charm. “I would have loved to have interviewed Sinatra. And, of course, the Queen! Just imagine what an interview she is. Think about all the people she has met and the circumstances she has met them in.”

So now that the ‘Parkinson’ set has been put away for the last time, never to return, I was curious as to how he feels looking back on his time in front of the camera, laughing with Billy Connolly, grappling with ‘that bird’ Emu and sparring with Muhammad Ali, as well as all the other captivating moments that were created by the man who turned the practice of two people sitting in chairs, chatting, into something quite magical?

After a short pause, Sir Michael leans back, shuffling around in his chair once again, and says, “I thought I'd fancy Meg Ryan more than I did. And vice versa (laughs). There was just a total lack of sympathy between the two of us.”

So what is it, I wondered, that separates those in the limelight from the rest of us, mere mortals in the background of life, rather than the forefront? “They have an indefinable quality that I describe as will power. If you look at Muhammad Ali, Nelson Mandela, Billy Connolly, there’s something that separates them from the rest of the human race. Although they are, of course, human, like the rest of us, they are special people, with an overwhelming drive to achieve something. I never had that drive. I just always wanted to be a good writer, a good journalist. That has been my motivation throughout my life.”

Despite being known as ‘the man who has met everyone’, there are a few, believe it or not, who escaped his charm. “I would have loved to have interviewed Sinatra. And, of course, the Queen! Just imagine what an interview she is. Think about all the people she has met and the circumstances she has met them in.”

So now that the ‘Parkinson’ set has been put away for the last time, never to return, I was curious as to how he feels looking back on his time in front of the camera, laughing with Billy Connolly, grappling with ‘that bird’ Emu and sparring with Muhammad Ali, as well as all the other captivating moments that were created by the man who turned the practice of two people sitting in chairs, chatting, into something quite magical?

“My father, being a miner and a Yorkshire man, once said to me he didn’t really understand what I was doing. He was waiting for the time I had a proper job. He always wanted me to play cricket for Yorkshire and because I didn’t, he thought I was a failure.

“Just before he died, he said to me, ‘you've had a good life haven't you? You've interviewed some beautiful women and you've made a bit of money. Well done. But think on, it’s not like playing Yorkshire cricket is it?’

“And what he was defining was the difference between fame and immortality. I mean if you play cricket for Yorkshire you’re immortal. But if you're merely famous it doesn't matter.”

‘Parky’ My Autobiography, by Michael Parkinson, Published by Hodder & Stoughton.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)